The voice behind the veil

The debate about the face veil, and more generally the acceptability of other forms of female Muslim attire in the West, is not a novel one. Muslim notions of modesty, have often been subverted and colonized by patriarchal practices seeking to restrict women's autonomy. As such, the veil issue has mobilized social forces inspired by liberalism and feminism and generated valuable criticisms of patriarchy in Muslim communities. On the other hand, the 'out of place' look of veiled women in European public spaces has provided fertile ground for the transformation of the veil issue into a potent mobilizing symbol for xenophobic, right wing forces only too happy to jump into the bandwagon of the secular, liberal and feminist opposition to the veil and, often, to incorporate these discourses into their own arguments. In this way, for example, spokespersons of the conservative Spanish Partido Popular such as Alberto Fernandez, a Barcelona city councillor, shed crocodile tears about the dignity of Muslim women: "The use of the burqa and niqab undermines the dignity and freedom of women", Fernandez said on his website commenting on the recent Barcelona niqab ban which he considers to be "a half-measure”.

In the UK the niqab, has been posited in public discourse as the visible symbol of the perceived lack of integration of the Muslim community into British society and has therefore been associated with the whole debate over the perceived failures of multiculturalism as Jack Straw’s (who was at the time leader of the House of Commons) 6 October 2006 column in the Lancashire Telegraph indicated when he described the veil as "such a visible statement of separation and of difference". But this is not an exclusively British debate; in other European countries similar public discussions have been underway for quite a long time. Belgium and France have moved fast towards introducing legislation banning the face cover on the grounds that the veil constitutes a “prison for women” and a “sign of their submission to their husbands, brothers or fathers” while Spain is moving towards a similar direction by preparing new legislation to curtail the use of the face veil. Similarly, the Netherlands is revisiting an earlier discussion on the desirability of a ban.

In all these debates the proponents of the ban use arguments that identify in the veil patriarchal oppressive practices that are detrimental to the dignity of Muslim women, or safety and security problems or, finally, barriers to intercultural communication and social cohesion.

What is remarkable however, and should be noted, is that this debate is also one conducted over the absence of the women in question, as it largely leaves the affected women in a position of aporia, voiceless and powerless in the midst of a cacophony of opinions offered by western politicians, human rights activists and feminists on the one hand, and Muslim community leaders on the other: veiled women constitute the battlefield between abstract discourses of emancipation and discourses of cultural autonomy that emphasize the lack of competence of the part of liberals and feminists to criticize an essentially reified 'muslim' culture and tradition.

It is true, that behind the veil one can find women that are isolated, lonely, abused and oppressed. In such cases, the veil can dissimulate suffering and silence cries for help. In such cases we need to devise ways of listening, of intervening and of empowering. On the other hand, considering the veil simply as a means and symbol of oppression may be misguided as it decouples it from its social-historical context. In the course of our research we have encountered numerous young women who experiment with covering their hair or face who have stressed in very articulate ways that this was a matter of choice and not coercion. Women have mentioned numerous reasons for covering or veiling themselves: affirming their identities as young Muslims, protesting against assimilationist ideologies and practices, expressing their religiosity and protecting themselves from the objectification of the male predatory gaze.

Before resorting to the platitudes that are rehearsed time and again in order to bring about a blanket ban on the niqab, it is worth considering the voices of women who stress the right to choose as the primary reason for wearing it:

As these interview excerpts indicate, these young women have no difficulty in bringing together Islamic discourses about modesty and the language of choice, needs and human rights which originates in the discourse of the enlightenment that Europeans usually juxtapose to Islam as belonging to a totally distinct intellectual and cultural tradition. Of course, one can always question and disagree with some of these rationalizations of veiling but the fact remains that veiling in these instances is understood as a positive assertion of rights and affirmation of identities.

In addition to this development of a discourse of reclaiming the niqab as a choice and right, this onslaught against women wearing the veil has been met with other, alternative, responses not only by the affected women but also by Muslim women in general that attempt to create enunciation spaces that enable women to offer alternative definitions and perspectives about themselves, and their relationship with Islam. One of the strategies employed can be described as what we call normalization: Over the past few years, a Muslim lifestyle and fashion industry has developed in Europe and, more broadly, in the West and has contributed to attempts to redefine and reclaim the face veil and other aspects of Muslim attire and femininity from the western discursive association with oppression and subordination.

Many glossy colourful lifestyle magazines with articles on love, what it means to be a woman, marriage, having kids, marital discord, house decoration, food and, of course, fashion, cautiously bring to the public discussion a host of issues that have, in their majority, traditionally been confined to the private or more intimate domain among Muslim women, and Muslims in general. While these magazines affirm Islam as the leitmotif of these discussions, they bring these issues out of the jurisdiction of Islamic scholars or of female elders to new public spaces where readers can form their own opinions and interpretations not only on issues such as relationships or lifestyles but also on Islam itself.

In these new contexts, several companies offer fashion products that adhere to 'Muslim tradition' but still provide women with choice and the possibility to express aspects of their own selves through it. It is interesting to see how women discuss fashion trends and styles, the use of accessories and clothes for different occasions such as parties, formal events, casual settings etc in social media such as Facebook or Myspace, personal blogs and in everyday conversations, or how they customize their attire be that a niqab or a hijab or abaya.

This process, interestingly, entails fine balancing between the Islamic and the Western - whatever these terms may mean. For example, most magazines or advertising adhere to the principle of non-depiction of human likeness and avoid showing faces, opting for photographs where faces are barely visible or the use of mannequins; then again, material developed for younger women might show human faces but still does this with respect for the principle of modesty. And even the very notions of modesty are reconfigured and reconciled with those of beauty and choice as a host of colours, styles, and accessories to liven up and personalize women's attire are on offer.

These developments constitute modest, mundane, everyday attempts to decouple 'Islamic' notions of femininity from assumptions of subordination, oppression and lack of dignity. They also destabilize and reconfigure the very notions of the Islamic and the Western; by acquiring a central position in these new enunciation spaces, Islam is progressively 'routinized' and reinterpreted in a variety of ways. Similarly, the articulation of 'being Islamic' in terms of human rights and citizenship and through the reinterpretation of key Islamic notions such as that of modesty through their coupling with beauty and choice, the assumed rigid boundaries between the Islamic and the Western are relativized and blurred.

This note draws upon material from a research project conducted over the past few years on the construction of public spaces and civic networks by European Muslims - – the highly diverse but also interlinked attempts of European Muslims to assert their right to define themselves as Muslims and, at the same time, to (re)define Islam.

|

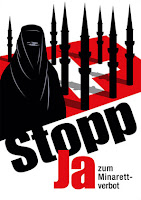

| A veiled woman next to the minarets both potent symbols of the 'islamization' od Switzerland in the recent minaret referendum |

|

| Muslim Fashion Show |

What is remarkable however, and should be noted, is that this debate is also one conducted over the absence of the women in question, as it largely leaves the affected women in a position of aporia, voiceless and powerless in the midst of a cacophony of opinions offered by western politicians, human rights activists and feminists on the one hand, and Muslim community leaders on the other: veiled women constitute the battlefield between abstract discourses of emancipation and discourses of cultural autonomy that emphasize the lack of competence of the part of liberals and feminists to criticize an essentially reified 'muslim' culture and tradition.

It is true, that behind the veil one can find women that are isolated, lonely, abused and oppressed. In such cases, the veil can dissimulate suffering and silence cries for help. In such cases we need to devise ways of listening, of intervening and of empowering. On the other hand, considering the veil simply as a means and symbol of oppression may be misguided as it decouples it from its social-historical context. In the course of our research we have encountered numerous young women who experiment with covering their hair or face who have stressed in very articulate ways that this was a matter of choice and not coercion. Women have mentioned numerous reasons for covering or veiling themselves: affirming their identities as young Muslims, protesting against assimilationist ideologies and practices, expressing their religiosity and protecting themselves from the objectification of the male predatory gaze.

| |

| Sisters Magazine: the magazine for fabulous Muslim women |

Niqaab has given me a feeling of power over myself, not just my outer, physical being but my inner mind also ... I can now say I'm a woman of honour and dignity that no one should dare to mess with... From Al-Muhajabah's Islamic Pages

The Niqab is a choice whether it is required or not but in the civilized world the right to exercise personal choice ought to be protected. This is what is some thing called civil rights enjoyed in civilized societies Hayfa, 27 (Germany)

Although I consider myself a feminist muslim who usually does not cover, [nonetheless I think] … freedom is peculiar when it only allows you to make whatever choice the state wants Aminah, 29 (British living in France)

I started covering as a matter of choice … I do not want others to tell me how they want me to be. Nadifa, 28 (UK)

I choose to wear it. Not every day, just now and again. But when I do wear it, it is entirely of my own will. No one is forcing me. If they make me take it off, they’ll be taking a part of me. Amina, 21 (France)

As these interview excerpts indicate, these young women have no difficulty in bringing together Islamic discourses about modesty and the language of choice, needs and human rights which originates in the discourse of the enlightenment that Europeans usually juxtapose to Islam as belonging to a totally distinct intellectual and cultural tradition. Of course, one can always question and disagree with some of these rationalizations of veiling but the fact remains that veiling in these instances is understood as a positive assertion of rights and affirmation of identities.

In addition to this development of a discourse of reclaiming the niqab as a choice and right, this onslaught against women wearing the veil has been met with other, alternative, responses not only by the affected women but also by Muslim women in general that attempt to create enunciation spaces that enable women to offer alternative definitions and perspectives about themselves, and their relationship with Islam. One of the strategies employed can be described as what we call normalization: Over the past few years, a Muslim lifestyle and fashion industry has developed in Europe and, more broadly, in the West and has contributed to attempts to redefine and reclaim the face veil and other aspects of Muslim attire and femininity from the western discursive association with oppression and subordination.

Many glossy colourful lifestyle magazines with articles on love, what it means to be a woman, marriage, having kids, marital discord, house decoration, food and, of course, fashion, cautiously bring to the public discussion a host of issues that have, in their majority, traditionally been confined to the private or more intimate domain among Muslim women, and Muslims in general. While these magazines affirm Islam as the leitmotif of these discussions, they bring these issues out of the jurisdiction of Islamic scholars or of female elders to new public spaces where readers can form their own opinions and interpretations not only on issues such as relationships or lifestyles but also on Islam itself.

|

Poster publicizing debate on Muslim women's oppression |

This process, interestingly, entails fine balancing between the Islamic and the Western - whatever these terms may mean. For example, most magazines or advertising adhere to the principle of non-depiction of human likeness and avoid showing faces, opting for photographs where faces are barely visible or the use of mannequins; then again, material developed for younger women might show human faces but still does this with respect for the principle of modesty. And even the very notions of modesty are reconfigured and reconciled with those of beauty and choice as a host of colours, styles, and accessories to liven up and personalize women's attire are on offer.

These developments constitute modest, mundane, everyday attempts to decouple 'Islamic' notions of femininity from assumptions of subordination, oppression and lack of dignity. They also destabilize and reconfigure the very notions of the Islamic and the Western; by acquiring a central position in these new enunciation spaces, Islam is progressively 'routinized' and reinterpreted in a variety of ways. Similarly, the articulation of 'being Islamic' in terms of human rights and citizenship and through the reinterpretation of key Islamic notions such as that of modesty through their coupling with beauty and choice, the assumed rigid boundaries between the Islamic and the Western are relativized and blurred.

This note draws upon material from a research project conducted over the past few years on the construction of public spaces and civic networks by European Muslims - – the highly diverse but also interlinked attempts of European Muslims to assert their right to define themselves as Muslims and, at the same time, to (re)define Islam.

Comments

Post a Comment